Building a Thinking Classroom Framework: Putting It All Together

For the past several weeks I have been reviewing Peter Liljedahl’s book, Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics. His book contains research and information on thinking tasks, classroom logistics on giving thinking tasks, how to provide feedback, grading and how to help students transfer what they learn to other assessments. All these different pieces that Liljedahl discusses in his book build autonomy and self-efficacy in students with the ultimate goal of students being responsible for their own learning. If this teaching strategy interests you, then you should know that the order you present the pieces of a thinking classroom to your students matters.

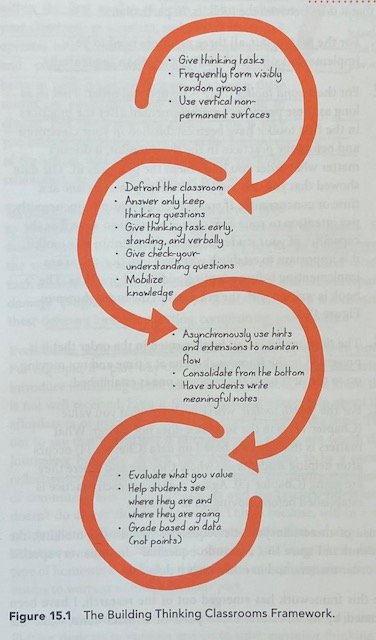

Liljedahl breaks down all the pieces of a thinking classroom into a framework that he calls Building Thinking Classroom Framework (see image below, p. 281). The framework consists of four different groups, or toolkits. How and when the toolkits are implemented matters. In addition, how the practices within a toolkit are implemented matter as well, (pp. 281, 282).

Building Thinking Classroom Framework, p. 281

The first toolkit consists of three thinking classroom practices. These practices need to be implemented in the order they are listed in order to disrupt the traditional model and norms of a classroom. By doing so, teachers can create new patterns and habits in their classroom for students. These practices include giving thinking tasks, working in randomly assigned groups and working on vertical, nonpermanent surfaces, (pp. 282, 283).

The second toolkit consists of six different practices that can be implemented in any order as long as they follow the implementation of the first toolkit because they help fine tune the first toolkit practices. This second toolkit focuses on changing teaching practices. It is not effective at disrupting norms and creating new habits on its own. It includes defronting the classroom, answering only those questions that keep students thinking, verbally assigning thinking tasks while standing together as a group, using specific questions for students to check their understanding and mobilizing knowledge between students and groups, (pp. 282, 284-285).

The third toolkit consists of three practices that need to be implemented in order. This toolkit includes asynchronous use of hints and extensions to maintain flow, consolidate learning from the bottom and have students write meaningful notes. Each practice needs to be solidified before adding in the next one, (pp. 282, 285-286).

Finally, the fourth toolkit consists of the final three practices that triangulate data and provide a more complete picture of students’ ability. These practices include evaluating what you value as the teacher, helping students see where they are and where they are going and grading based on data not points. The first two practices can occur in any order, but the grading based on data must occur after helping students see where they are and where they are going, (pp. 282, 287-288).

Liljedahl stresses that when introducing the thinking classroom framework, each practice needs to be established before adding in the next practice. Adding in a practice too soon or out of order can undermine the process and progress for your students. For example, introducing grading before helping students see where they are and where they are going will shift the emphasis away from outcome based learning. Likewise, introducing meaningful notes before the consolidation process will be ineffective because meaningful notes are a tool for students to put their learning from the consolidation process in their own words.

Regardless of the order, I think one of the critical findings of Liljedahl’s research is the transference he and the teachers observed as they implemented certain practices in the framework progression. Like every other classroom, the teachers and Liljedahl were observing students' increased ability to solve problems and demonstrate their learning and growth in the classroom during the tasks. The students were not showing the same level of competence when given assessments. However, as teachers implemented check your understanding question (toolkit two), consolidation from the bottom, meaningful notes (toolkit three), and helping students see where they are and where they are going (toolkit four), this imbalance in performance between classroom practice and assessment began to dissipate. Liljedahl surmised that the practices helped students move from a point of understanding and knowing within the group collective to an independent understanding and knowing that was generalizable, (pp. 288 - 289).

For me as a teacher, the information Liljedahl gained on transference is critical. As a Special Educator, I frequently had students who could complete grade level tasks with me, but could not do the same work in their classroom. Generalization was difficult. With some students, I used their daily math from their classroom to help with transference. With other students, I kept referencing and showing them what they were responsible for at their grade level. My results were mixed. I think having the tools of the thinking classroom framework, especially the practice of where you are and where you are going, would make a huge difference in the learning process, progression and generalization for my students.

© 2025 Linda Patrell-Kim